How to identify added and hidden sugars on nutritional labels

Americans are eating and drinking too much sugar. To live healthier, longer lives, we all need to move more and eat better. There is no doubt about that statement, it alone is not the cure for obesity, but if you add getting fewer calories from added sugars, you might just have the answer. The problem with sugar is that adding it to food adds empty calories. Empty calories pad your waist with little to no nutrition added.

Sugar is a natural ingredient that has been part of the human diet for thousands of years. They are found in almost all plants and sugars are carbohydrates that provide energy for the body. The most common sugar in the body is glucose. Our brains and most of our bodies need it to function properly. Some of the sugar we consume is found naturally in foods while a large portion is added during cooking and processing. Unfortunately, our bodies do not utilize all sugars as efficiently but we will discuss that more below.

You cannot go online or watch the news without being reminded of the evils of sugar. Today the average adult consumes about 22 teaspoons of sugar per day and about 150 pounds of this white stuff per year. Sugar has been blamed for just every disease to include ADHD, type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, metabolic syndrome, and obesity. Sugar is in just about everything you eat, and it is nearly impossible to avoid. What makes avoiding sugar so difficult for most people is caused by two issues. One source of confusion is the fact the labels are purposely confusing and manufacturers hide sugar dividing the sugar into several different types. The second source of confusion is not all sugar is inherently harmful, and in reality, our bodies actually need some sugar to function. Sure, you can make sugar but not at the level your body needs it for energy.

So what is sugar? Sugar, as most of us are referring, is sucrose. Sucrose is that white stuff that sits in the bowl on many of our dining room tables. Sucrose is a simple carbohydrate that provides calories for your body to use as energy. It is a two-ring simple sugar or disaccharide that is one glucose molecule and one fructose molecule. It is found in most plants, but most of our sucrose comes from beets or sugar cane.

So sugar is just sucrose? Not exactly. Sugars, in the science of medicine and nutrition, is a group of compounds that are made of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen in the form of rings. Sugar compounds include the monosaccharide or single ring sugars and disaccharides or two ring sugars. The monosaccharides include fructose, galactose, glucose (dextrose), and mannose. The disaccharides include lactose (galactose and glucose), maltose (two glucose units), and sucrose (glucose and fructose). There are other sugars, but these are the most nutritionally significant.

So all sugars are just sugars, right? How does all this sugar get into my food? Some sugar comes naturally in the food we eat. For example, strawberries contain fructose naturally. There are two main types of sugar. Natural sugar is found in whole, unprocessed foods, and added sugar is found in processed foods, candies, baked goods, sauces, and drinks. Fruits, vegetables, dairy, and some grains contain natural sugars. Fructose is a natural sugar found in most fruit. Lactose is the natural sugar found in dairy products. Added sugar includes the sugar you add to food as you cook at home. Calories from sugar are empty because it provides little to no nutritional value. Sugar is added to food to add flavor, add color, create texture or consistency, and/or allow the yeast to ferment and bread to rise or create alcohol. Some foods such as Coco-Cola are almost entirely added sugar. In fact, a 12-ounce can of Coca-Cola has nearly ten teaspoons of sugar.

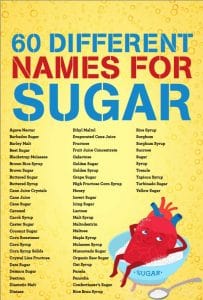

So what is an added and hidden sugar? These are the sugars manufacturers add to foods to create a more attractive flavor. Look at your red pasta sauce or ketchup. Odds are it has sugar added. Manufacturers often hide it by calling it another name. They may even add them under several different names, so sugar is not in the top ten ingredients, but if you add them up, that is a lot of sugar. For example, my ketchup has both high fructose corn syrup and corn syrup listed in the ingredients. One canned pasta sauce in my cabinet had three sugars listed in the ingredients, and those are high fructose corn syrup, corn syrup, and sugar. Each serving of either product has over 5 grams of sugar or more than the equivalent of 1 teaspoon of the white stuff. Examples of different sugar names that may appear in the ingredient list is located in Figure 2 (60 Different Names for Sugar from thatsugarfilm.com).

As I indicated above, fructose is the type of natural sugar found in modest amounts in real foods like fruits and even vegetables. Fructose is generally not something to worry about when consumed as part of a balanced diet because it’s metabolized and turned into fat so your body can use it. The problem is when you take in too much fructose such as you woo by drinking soda or processed foods that contain high fructose corn syrup. Our bodies are just not meant to take in that large of a volume of fructose. For example, let’s consider the strawberry mentioned above. Each cup of strawberries contains just over 4 grams of fructose, and thus it would take 5 cups of strawberries to consume the same amount of fructose that is found in the average soda. We all know soda has a lot of sugar in it. The real problem lies in consuming hidden added sugar in foods such as spaghetti sauce, ketchup, sweetened yogurts, cereals, snack bars, juices, and other drinks. The primary difference between something like fruit and soda is soda lacks the fats, fiber, and protein to slow the absorption of the sugar molecules, so you get a rush of sugar instead of slow, sustained absorption.

Manufacturers have often argued that sugar is natural and the whole problem is calories and not sugar. In fact, there are a plethora of research articles out there to support their belief that sugar is not to blame for obesity. The problem with the research is the same problem with most research, and that is the source of funding. Nearly all of the research pointing away from sugar was funded by either soft drink companies or the sugar manufacturer. It sends a message of bias when you fund the research that sends the message you need to sell more products.

How much-added sugar can I have? You need to eat as little as possible. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that men and women limit themselves to 9 and six teaspoons per day respectively (Figure 3)[1]. This recommendation is refreshing because many of the AHA stamps on foods seem to be suspect based on the nutritional value of many of the foods that showcase it.

Is added sugar associated with obesity? Yes. There are a number of studies that show that obesity and sugar consumption are indelibility tied to one another. As early as 2001, evidence started mounting to point to sugar as the culprit for childhood obesity[2] and was followed by additional research to back up the previous study[3]. This was followed by evidence linking sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and heart disease and type 2 diabetes[4]. People who consume 1 to 2 cans of sugary drinks a day have a 26% greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes than people who rarely have such drinks[5]. Yet another research study found a significant tie between sugar-sweetened beverages and diabetes type 2, heart disease, and obesity[6]. The evidence is clear: excess added sugar is tied to obesity and diabetes type 2 and the beverage industry continues to claim that moderation is the key to consumption. For more information, read my articles on pre-diabetes and metabolic syndrome.

The bottom line: You need to read the labels of the foods and ingredients you buy. Added or hidden sugar can be quite difficult to identify on the labels, and it only adds empty calories. Some products may just have a small amount of sugar, but others have many teaspoons. Experts I have spoken to suggest that anything under 5 grams of sugar per 100 grams is okay to keep in the pantry. You might eventually cut back on these foods, but as a start, be kind to yourself and take the gentle approach.

Be the first to comment on "Hidden Sugar, Visible Weight"